A journey through time

Seventy years on from the end of WW2, Ian Baird visits the atmospheric remains of two Dorset fishing villages, cleared by the government for use as practice for the D-Day landings.

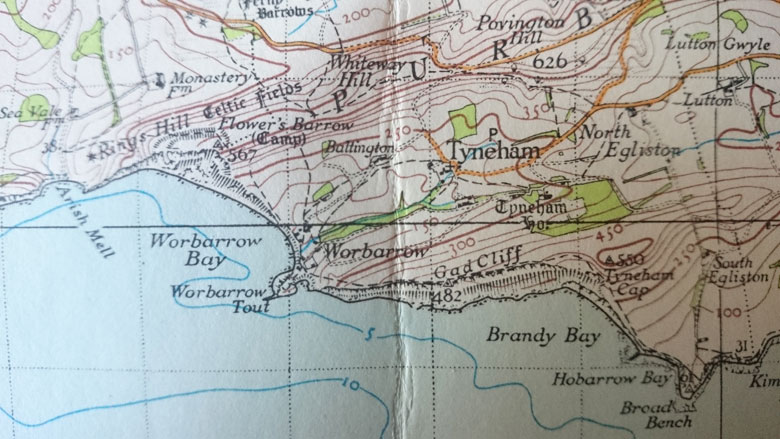

It’s a bright spring day, and I’m walking from East Lulworth to Tyneham and Worbarrow Bay. I have with me a 1930 map of the area, the most up to date for where I am going – quite appropriate for what is in many ways a journey back in time.

Nobody lives in Tyneham and Worbarrow Bay today – but they used to. In the cold winter of 1943, the local fishing families in the two villages here received a small brown envelope informing them that they had a fortnight to leave. The whole area was being requisitioned by the Army to practice for the Normandy landings.

Resettlement was made wherever the government could find local accommodation. The deserted villages became witness to mock invasions of British and Allied troops: you can still see the mangled wrecks of tanks nearby. After centuries of life here, the thriving fishing community had gone in the blink of an eye. The order was meant to be temporary, but the families were never allowed back.

The beach hamlet of Worbarrow is reached by a path running alongside Gwyle Stream. There were nine homes there, mainly occupied by the Millers: a family of fishermen who worked directly from the beach and had done so in an unbroken line stretching back to 1678. As I wrote in March, the Millers – David, Joe and Levi – still fish these waters today out of Lulworth, making them the longest continuously fishing family in the whole of the country.

The 1851 census lists 18 Millers living in this tiny hamlet. Jack and Tom Miller owned a crab and lobster boat, later named Witch of Worbarrow (an inspirational, life-changing boat for me), from which they seine-netted mackerel as well as potting crab and lobster. Their catch was bought by the Wareham fish merchants and sent by train to London as well as feeding the village. Jack and Miggie Miller lived in Rose Cottage, Henry and Louisa at Hill Cottage and Joseph Miller’s family in Sea Cottage, almost on the shoreline.

“When I was young the remains of the cottages were still there,” says Joe Miller (pictured above) today. “And there was a boathouse too, still standing. It still had its doors and if you peeked inside there was a boat in there.” Today that’s all gone, and only the outlines of the houses remain at Worbarrow.

In Tyneham the walls remain, windowless and roofless, but both the Church of St Mary the Virgin, which sits on a tiny knoll in the centre of the village, and the school are intact. The school is preserved as it was when the children left, their names still on the coat pegs.

Leaving aside the human tragedy, this is a beautiful and timeless place, where the presence of its former inhabitants can still be felt. The church has a wonderful display of village history and the people who lived here. It was also here that 42-year-old Helen Taylor, the last villager to leave, pinned a note on the church door intended for the Army officer who was to take possession of her precious village. She didn’t know it, but she had unwittingly written Tyneham and Worbarrow’s epitaph:

“Please treat the church and houses with care. We have given up our homes where many of us lived for generations to help win the war to keep men free. We shall return one day and thank you for treating the village kindly.”

Ian Baird is a self-employed boat builder on Dorset’s Jurassic Coast. He has a workshop where he makes all kinds of nauticalia both from new and recycled materials, especially native woods. He also manages a coppice woodland in Dorset for conservation and greenwood forestry products, as well as The Galley Café Mobile Canteen with his friend, chef Keian Gillett of the Galley Café in Lyme Regis, offering fishy treats to hungry Dorset folk.