Against all odds

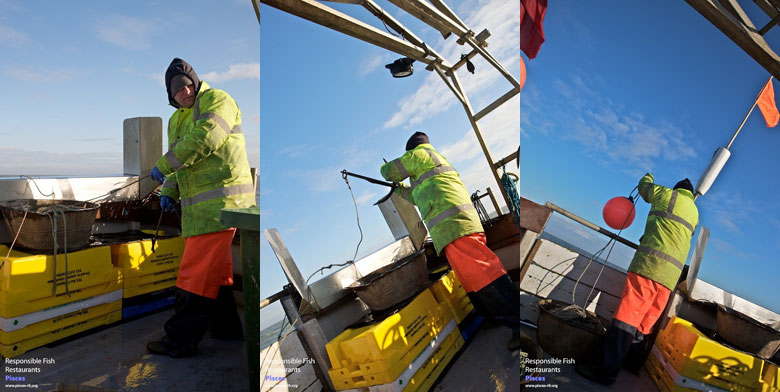

Never easy, times have been particularly tough lately for Britain’s low-impact small boat fleet. Mike Warner meets lifelong Suffolk fisherman Bill Pinney to learn about the challenges he has to overcome daily to bring in the catch.

It’s all too easy sitting here in a warm office, Labradors by my feet, waxing lyrical and enthusiastically eulogising about the abundance of amazing produce that our inshore waters harbour. It’s only marginally more strenuous to drive to the plethora of local fishmongers and restaurants to sample what bounty the shallow seas of our coastline have yielded.

Of course, I’m passionate about it and nothing gives me greater pleasure than committing my, sometimes, rather romanticized, thoughts to paper; however I do feel we all, at times, need to suffer a sharp reality check and take the time and effort to mine down into the detail of what actually occurs at the leading edge, at the coal face, and to understand, more fully, the many criteria that need to assemble before end products such as fresh and sustainably caught fish and shellfish are realised and brought within our reach.

It’s with these thoughts in mind, that I decided to do just that and investigate exactly what pressures, restrictions and obstacles are faced by the under-10m fleet around our coastline and how they cope while trying to maintain supreme quality for their customers, but also sustain their livelihoods.

As an example, I chose the tiny Suffolk fishing community of Orford and made my way there last week to talk to Bill Pinney, owner of Pinneys of Orford, about those very things and to try then to empathise with the local inshore fishing community, not just there, but all around the country.

Bill Pinney has been fishing all his life. His father, Richard, arrived in Suffolk after the Second World War, settled in Orford and resurrected the cultivation of oysters in the backwaters of the River Ore. This proved successful and Richard turned his attention to commercial fishing, developing a smokehouse, and a highly successful restaurant. Today the family operate two longlining and potting boats, the smokehouse, a shop, just off Orford Quay, and the Butley Orford Oysterage on the village square, which is where we meet.

In the back room of the Oysterage, over coffee, I begin to quiz Bill on exactly what pressures his business is facing, purely in terms of its ability to catch and land fish. He considers each question very carefully before replying earnestly and with an air that suggests to me that he has long forgotten more than I’ll ever know about the subject.

The first and immediate problem is actually being able to land the fish that they catch, using the low-impact methods the Pinneys employ. Longlining with baited hooks and bottom drift netting (they don’t trawl) are the least environmentally damaging and supremely selective methods, available. The prime target species are cod, skate (roker), soles and bass.

It is instantly apparent, though, that although there are fish there to catch, frustratingly, when catch limits are applied – set out by the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) – it can mean, in the case of skate, that the 200kg monthly limit can be easily reached in under a good day’s fishing. Bill tells me that the local waters off the Suffolk coast are full of skate at present and yet before Christmas the skate fishery was actually closed. Closed too for spurdog (rock eel/huss) and has remained so for some considerable while now, although again that particular species swims in abundance.

I sense an undercurrent of resignation from Bill, as this is the type of legislation that has to be accepted, but coupled with that is a real and tangible contempt, as he lists out the other factors that all go to make the lives and businesses of those men and women who operate our under-10m fleet that much harder to manage.

Wind farm construction (and associated cable laying), coastal dredging and the dumping of estuarine silt, Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs), the ill-thought-through Common Fisheries Policy, discards and of course the vagaries of the climate, resulting in adverse weather and water temperature changes, are just but a few of the factors these hardy souls are facing every day of their working lives. And then, of course, there’s no guarantee on price.

Expanding on some of these issues, Bill explains that the perpetual dredging of shipping channels and offshore gravel extraction are probably one of the biggest threats to his own local fishing grounds and their habitat. “The trouble is,” he sighs, “that we’re up against bodies such as the Crown Estate and where gravel extraction is the issue, the amounts involved in revenue are colossal.”

The dredging too causes huge physical knock-on effects. “The silt from the dredging is dumped from barges offshore, but still only in 40m of water,” he explains. “And then they do it at slack water too, when there is no tide to aid dispersal.” The result is that mud and silt is deposited directly on top of any natural habitat with dire consequences for the ecosystems involved. Slowly but surely then, continues the encroachment on to the fishing grounds.

On MCZs Bill appears a little more accommodating. “Would they have much impact?” I enquire, knowing well that the proposed Alde & Ore MCZ – for the protection of the breeding population of smelt (Osmerus eperlanus) and as a nursery area for other species – is currently on hold, as DEFRA requires further evidence to support the designation.

“I believe in theory, there could be benefits for the habitat involved,” says Bill. “As long as it doesn’t then become the thin end of the wedge and lead to more extensive exclusion zones, that, in turn, limit where we’re able to operate and what we can land.” It’s abundantly clear as the conversation continues, that the MCZs have to be designated for the right reasons and scientific evidence must be supported by detailed research, including first hand evidence from local fisherman with knowledge of their waters.

At this point I’m assuming that we’re nearly done on the pressures and difficulties facing the inshore fleet, but not so. “Of course, once we’re at sea and fishing we then have loss of our gear to contend with,” says Bill. “We daren’t shoot anything outside the 12 mile limit, as it just gets swept up by foreign beam trawlers who’ll run straight over it as they scour the bottom.”

Foreign boats also get a mention for another reason, namely, the Dutch-developed and highly controversial practice of “pulse trawling” an electro-fishing method of trawling the bottom using electrical current to disturb the fish, rather than ground chains. “Although it’s less destructive to the seabed, the electrical pulses target all fish no matter what class size, with significant negative results, as large numbers of fish outside the trawl range are affected too and end up dead, rather than in the net,” says Bill.

I’m now conscious of the time I’ve spent with Bill and abundantly aware that a lot of our conversation portrays quite a gloomy picture. “So what about the future?” I venture. “What change(s) would you like to see implemented to secure a better deal for the under-10s?”

Bill doesn’t take long to reply. “We need realistic minimum landing sizes,” he says, “particularly for all the demersal (or bottom feeding) species we catch”, such as cod, roker, soles, brill and turbot. “It’s just ridiculous that, so many small (juvenile) fish are able to be landed. The methods we employ take this into account, as small fish can be invariably returned, but that isn’t reflected with some netting methods, unless you use a bigger and more conserving mesh size.”

This would hopefully then lead to an increase in the class size of fish landed, through lower juvenile mortality. It all seems to make a massive amount of sense and I’m excitedly aware that I’ve already learned more about the industry in an hour than I have in many years, from talking to a man who, not only has veins that flow with saltwater, but has a deep-seated passion for and a progressive and hugely detailed understanding of his craft. A true artisan.

We draw the conversation to a close and I thank him enormously for giving up his time for me. As I leave the Oysterage I reflect on my own passion for the subject and how enriched it can become by talking to people such as Bill Pinney. But there’s so much more to learn and so many more people to meet. I can’t wait for the next encounter.

To find out more about Bill Pinney’s restaurant (Butley Orford Oysterage), shop (Pinneys of Orford, also online), Butler Creek oyster beds and smokery, visit: www.pinneysoforford.co.uk. Many thanks to the Pisces-RFR photo library for allowing us to use their pictures, which were taken on two visits to Orford and aboard Jolene during the months of February and April: www.pisces-rfr.org.

Mike Warner is an ardent seafood fan who blogs at A Passion for Seafood. He is based in Suffolk and finds inspiration from the diversity of life in Britain’s inshore and shallow seas. Mike is a supporter of the under-10m fishing fleet, advocate of sustainably-caught fish and shellfish, and fount of maritime knowledge.