Christmas at Fish Hall

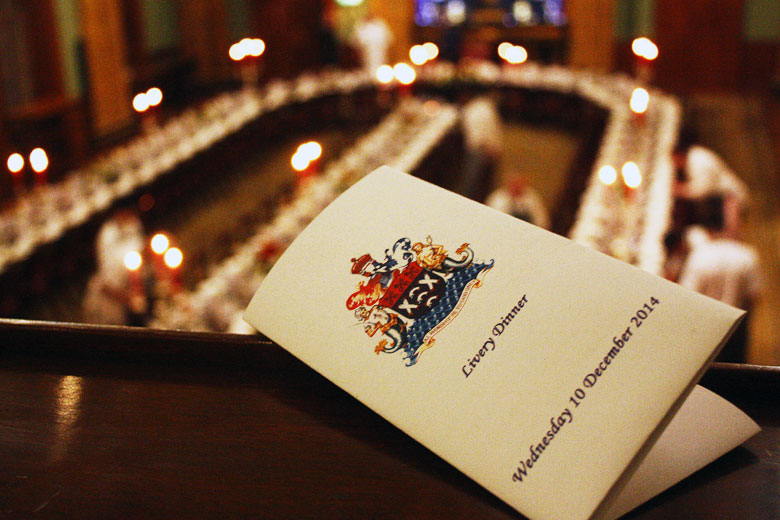

Our round-up of Christmas traditions wouldn’t be complete without a visit to Fishmongers’ Hall, the HQ of the Fishmongers’ Company. So Rachel Walker went along to the Christmas Livery Dinner, a festive affair par excellence.

Turtle soup followed by fried smelts, salmon a l’Indostan, turbot and oysters – and all this before the beef, turkey with chestnut purée, ham, mutton and three dessert courses. It’s hard to imagine guests leaving hungry after the Fishmongers’ Hall Christmas party on Thursday 9 December 1880.

Fast forward 134 years, and there have been a few changes. Today, there is no turtle soup and the French menus that were considered chic back in the day have become thoroughly English. But really, the most astounding thing about Christmas at Fishmongers’ Hall is not what’s changed, it’s how much has stayed the same. As we’ve written about before, this is an organisation that plays a key role in the modern fishing industry. But when it comes to observing traditions, the Fishmongers’ Company wrote the book.

There’s a real touch of Downton Abbey to the festivities here – and the scrupulous preparations that go before them. On a crisp winter’s morning, bright sunlight streams through the Greek revival windows in the Banqueting Hall, casting long shadows across the room. The chairs have already been set out and new wax candles fitted in the chandeliers.

Cleaners are polishing the tables which will seat 160 people, buffing their way steadily across swathes of polished wood, one minute in darkness, the next in fiercely bright diagonal light. Single notes hang in the air as a piano tuner adjusts the tensions of the Grotrian-Steinweg’s strings. Two men methodically check each light bulb, while another team starts working through pile upon pile of linen napkins, sculpting each one into the shape of a fan.

In the Court Drawing Room, florist Bridie Hastings is giving the final tweaks to a centrepiece arrangement: amaryllis, Casa Blanca lilies, spray roses, ilex berries, holly, dogwood and gilded eucalyptus, all from the New Covent Garden Flower Market. “Amaryllis take their time to open, so I’ve had these for nine days. The lilies will open in no time in a warm room like this,” she says, snipping away. “But if they’re all open, it can look a bit blousy, so it’s good to have some tightly closed buds for variety.”

Next door, another 12 table arrangements wait on a trolley. Like many of the others at work around me, Bridie has a practiced air of calmness, the result of many years of experience. “I left school when I was 15,” she smiles. “I never wanted to do anything else except be a florist, so here I am, 45 years in the industry.”

Head butler Jeff Stevelman has been at Fish Hall for 18 years. He’s one of the first to arrive in the morning, and the last to lock up at night. On special occasions like this, it can be a long day indeed. “I climbed out of bed at 5am this morning,” he says. He’ll be the last man standing at the end of the night too, only finishing work once the last guest has left.

His attention to detail is formidable: he knows exactly who will be doing what, when and where. So have ever been any disasters on his watch? “Hundreds,” he grins. “I could write a book on it.” But as he checks his watch and strides out of the room, leaving behind various teams all engrossed in different tasks, all running like clockwork, I’m not convinced.

Several floors downstairs, Peter Cobern, the custodian of the silver, is busy in his Aladdin’s Cave of a room. He talks me through some of the exquisite pieces which might be displayed tonight: a snuff box given to Sir William Lawrence in 1897 by Kaiser Wilhelm, and later bequeathed to the Fishmongers’ Company. “It was stolen once,” says Peter. “We recovered it, but some of the diamonds were missing,” he adds with a sigh.

He shows me the Anderson Cup, commissioned by a family who lost two sons in the First World War: the first on HMS Bulwark, which was destroyed by an accidental explosion that killed 745 men and left just 14 survivors; the second at the Somme. The third son died soon after the war. The cup depicts St George battling the dragon, its thrashing tail creating wave-like swirls, like a sea serpent. But enough of the tour. Peter is on a tight schedule, and he too has a long day still ahead of him. Not only does all the silver have to be carried upstairs and arranged on the tables, it also has to come back down again afterwards, to be checked in and locked up before his day ends.

As night falls, still more of the Christmas cast arrive. First, the Doggett Men, past winners of Doggett’s Coat and Badge, the world’s oldest continuous rowing race, which is overseen by the Fishmongers’ Company. Resplendent in traditional red coat, knickerbockers and buckle-shoes, each one holding an oar, they line the grand staircase, standing stock-still, like Guardsmen.

Next, the Gresham’s School Choir pour in, chirping and giggling with excitement. Since 1555, the Company has acted as a trustee of the Norfolk school, with Court members still making up much of its governing body. They take up their position in the hallway near the Christmas tree, singing Christmas carols as guests start to arrive.

Upstairs, chef Steve Pini and his team have already laid out the starter: cannelloni of sashimi tuna filled with Devonshire crab set on soured cucumber and shallots with Asian soy jelly. In time, the guests come through and find their seats. The lights dim, grace is sung and the feast begins…